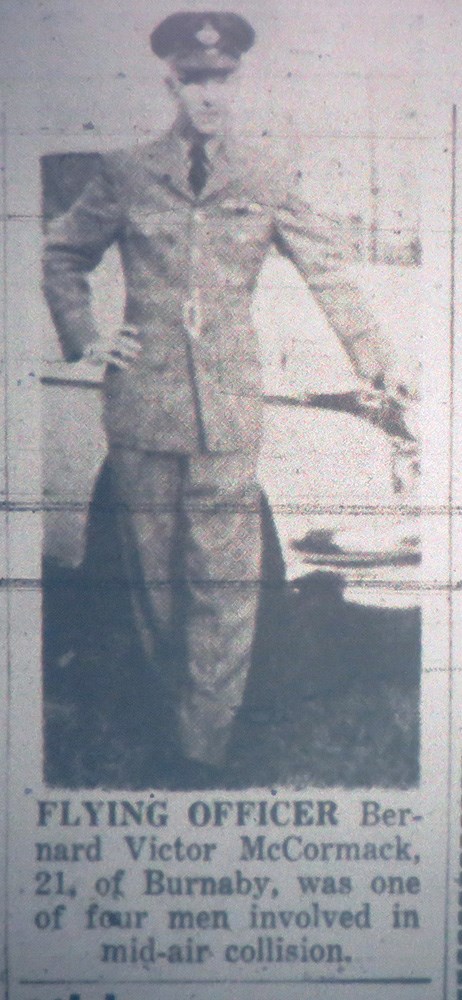

For retired pilot Bernie McCormack, the story of the airplane crash on Sunday, Jan. 13, 1957 in the dense brush at the northern end of Paradise Valley begins the day before the crash.

On Saturday, Jan. 12, 1957, Capt. Jim Burrows and McCormack were departing Vancouver Airport in a Trans-Canada Air Lines DC-3 for Victoria and were to turn around for a flight back home to Vancouver.

"We were in the mid-evening darkness of winter, and I commented on the radiation fog that was forming at ground level in the grass and across the taxiway. I could see that by the time we returned, it would probably be deep enough to prevent us from returning when we were scheduled back. I told Jim that I had planned to attend the wedding reception that evening of a very sweet and pretty stewardess friend, Betty Gibson, and that I had an accordion and some beer in the trunk of my car to accompany me," McCormack, now in his 80s, recently recalled to The Chief.

"Maybe we could fake a problem for a half hour or so and then wouldn't be able to depart. Jim laughed, 'Yeah, sure,' and then we departed. As we forecasted, our return flight was cancelled and we spent the night at the hotel in Sydney."

The next morning of that fateful day, Vancouver was still fogged in so the men took the scheduled flight out of Victoria to Seattle before heading back to Vancouver, which was by then enjoying a beautiful sunny day.

"I drove over to the Air Force (North) side of the airport after deplaning and, in the pilot's ready room, Flight Officer Ray Martin told me that all of the aircraft were booked — reserve squadrons 442 and 443 — but if I was interested, I could fly in the backseat of his T-33 to fly in formation with another T-33."

McCormack agreed and quickly changed into his winter gear, including boots, rather than remaining in his commercial airline uniform.

"That probably saved me from severe burns and possible death an hour or so later," McCormack recalled.

"The heavy insulation protected my arms and legs from the flames and also gave me some warmth while I was overnight in the snow."

Once suited up, the pair took off and were soon in two aircraft formation with the other T-33.

"Ray directed, ‘OK chaps, line astern,'" McCormack said.

That meant a tail chase or practice dogfight would ensue.

Shortly thereafter, flying above Squamish, the two T-33s collided and crashed.

The bodies of the navigator and pilot from the other plane — Burton Patkau, 27, and Roderick Atkins, 19 — were later recovered.

McCormack and Martin bailed out of their plane.

But the newspaper stories at the time got his escape wrong, McCormack said.

He did not eject. His ejection seat did not fire, so he hit the seat harness release and then pushed or kicked himself out.

This worked because his plane was inverted at the time the two planes collided, according to McCormack.

He was burned more severely than Martin because the fire was greater in the back seat, and also because he didn't have his flying gloves on.

Recently, Squamish locals uncovered what they believe is the wing of the T-33 McCormack was in when it crashed that cold, January day.

The wing was found in a ditch near the railway tracks on Government Road last month, buried deep in the mud. Speculation is that the wing either dropped off a train that was transporting it from the crash site to the city or that a local resident recovered the wing in the valley, hauled it out and discarded it at some point.

Regardless of how it ended up there, what happened to the plane's parts was the least of McCormack's worries when he landed in the forest that afternoon more than 70 years ago.

"I was in the bush on the side of Brandywine mountain with severe burns to my hands, wrapped in my parachute. I fired off flares — had to use my teeth," he recalled. It was extremely cold at times overnight, but as he waited to be spotted by search crews, he finally slept until he was awakened mid-morning by a whistle from a para-rescue fellow some distance away.

"I whistled back and was then helped, about 20 minutes later, to a small frozen lake, scrambled into a search and rescue helicopter, flown to Shaughnessy Hospital and then endured six months of skin grafting and repairs," he said.

There was no real trauma therapy in those days, but McCormack said he didn't suffer psychologically and was back flying shortly after leaving the hospital.

Currently in his early 80s and living in Coquitlam, McCormack remains in good health, he said.

"I exercise and jog at a high school track three or four times a week," he noted, adding he doesn't need to take any medication.

Asked what else he would like people to know about his experience, McCormack had a message for his military brothers and sisters as well as for civilians.

"We were trained for combat and the flying required to hone the skills required for the possibility of another war was inherently dangerous as demonstrated by our experience."

��