For the last two months of their life in the United States, José Alberto González and his family spent nearly all their time in their one-bedroom Denver apartment. They didn’t speak to anyone except their roommates, another family from Venezuela.

They consulted WhatsApp messages for warnings of immigration agents in the area before leaving for the rare landscaping job or to buy groceries.

But most days at 7:20 a.m., González’s wife took their children to school.

The appeal of their children learning English in , and the desire to make money, had compelled González and his wife to bring their 6- and 3-year-old on the monthslong journey to the United States.

They arrived two years ago, planning to stay for a decade. But on Feb. 28, González and his family boarded a bus from Denver to El Paso, where they would walk across the border and start the long trip back to Venezuela.

Even as immigrants in the U.S. avoid going out in public, terrified of encountering immigration authorities, families across the country are mostly .

That’s not to say they feel safe. In some cases, families are telling their children’s schools that they’re leaving.

Already, thousands of immigrants have notified federal authorities they plan to “self-deport,” according to the Department of Homeland Security. President Donald Trump has by stoking fears of imprisonment, ramping up government surveillance, and and transportation out of the country.

And on Monday, the allowed the Trump administration to strip legal protections from hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan immigrants, potentially exposing them to deportation. Without , even more families will weigh whether to leave the U.S., advocates say.

Departures in significant numbers could spell trouble for schools, which receive funding based on how many students they enroll.

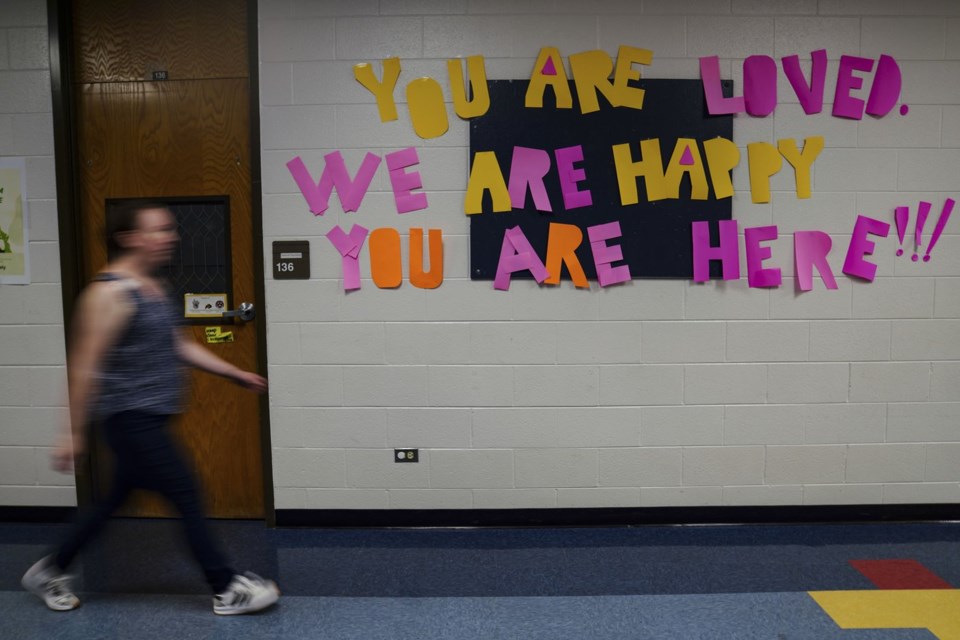

“The amount of fear and uncertainty that is going through parents’ heads, who could blame somebody for making a choice to leave?” said Andrea Rentería, principal of a Denver elementary school . “I can tell them as a principal that I won’t let anybody in this school. Nobody is taking your kid. But I can’t say the same for them out in the workforce or driving somewhere.”

Rumors of immigration raids on schools became a turning point

When Trump was elected in November after promising to deport immigrants and depicting Venezuelans, in particular, as gang members, González knew it was time to go. He was willing to accept the trade-off of earning just $50 weekly in his home country, where public schools operate a few hours a day.

“I don’t want to be treated like a delinquent,” González said in Spanish. “I’m from Venezuela and have tattoos. For him, that means I’m a criminal.”

It took González months to save up the more than $3,000 he needed to get his family to Venezuela on a series of buses and on foot. He and his wife didn’t tell anyone of their plan except the single mom who shared their apartment, afraid to draw attention to themselves. Telling people they wanted to leave would signal they were living here illegally.

They sent their children to their Denver school regularly until late February, when González’s phone lit up with messages claiming immigration agents were planning raids inside schools. That week, they kept their son home.

“Honestly, we were really scared for our boy,” González said. “Because we didn’t have legal status.”

In the months following Trump’s inauguration, Denver Public School attendance suffered, according to district data.

Attendance districtwide fell by 3% in February compared with the same period last year, with even steeper declines of up to 4.7% at schools primarily serving immigrant newcomer students. The deflated rates continued through March, with districtwide attendance down 1.7% and as much as 3.9% at some newcomer schools.

Some parents told Denver school staff they had no plans to approach their children’s campus after the Trump administration that had limited immigration enforcement at schools.

The Denver school district over that reversal, saying attendance dropped “noticeably” across all schools, “particularly those schools in areas with new-to-country families and where ICE raids have already occurred.” A federal judge ruled in March the district failed to prove the new policy caused the attendance decline.

Attendance dropped in many schools following Trump's inauguration

Data obtained from 15 districts across eight additional states, including Texas, Alabama, Idaho and Massachusetts, showed a similar decline in school attendance after the inauguration for a few weeks. In most places, attendance rebounded sooner than in Denver.

From 2022 to 2024, more than 40,000 Venezuelans and Colombian migrants or other assistance from Denver. Trump said he would begin his mass deportation efforts nearby, in the suburb of Aurora, because of alleged Venezuelan gang activity.

Nationwide, schools are still reporting immediate drops in daily attendance during weeks when there is immigration enforcement — or even rumors of ICE raids — in their communities, said Hedy Chang of the nonprofit Attendance Works, which helps schools address absenteeism.

Dozens of districts didn’t respond to requests for attendance data. Some said they feared drawing the attention of immigration enforcement.

In late February, González and his wife withdrew their children from school and told administrators they were returning to Venezuela. He posted a goodbye message on a Facebook group for Denver volunteers he used to find work and other help. “Thank you for everything, friends,” he posted. “Tomorrow I leave with God’s favor.”

Immediately, half a dozen Venezuelan and Colombian women asked him for advice on getting back. “We plan to leave in May, if God allows,” one woman posted in Spanish.

In Denver, 3,323 students have withdrawn from school through mid-April – an increase of 686 compared with the same period last year. Denver school officials couldn’t explain the uptick.

At the 400-student Denver elementary school Andrea Rentería heads, at least two students have withdrawn since the inauguration because of immigration concerns. One is going back to Colombia and the other didn’t say where they were headed.

School officials in Massachusetts and Washington state have confirmed some students are withdrawing from school to return to El Salvador, Brazil and Mexico. Haitians are trying to go to Mexico or Canada.

In Chelsea, Massachusetts, a 6,000-student district where nearly half the students are still learning English, a handful of families have recently withdrawn their children because of immigration concerns.

One mother in March withdrew two young children from the district to return to El Salvador, according to district administrator Daniel Mojica. Her 19-year old daughter will stay behind, on her own, to finish school – a sign that these decisions are leading to more family separation.

In Bellingham, Washington, two families withdrew their children after an Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid in early April at a local roofing company, where agents arrested fathers of 16 children attending Bellingham schools. Both families returned to Mexico, family engagement specialist Isabel Meaker said.

“There’s a sense, not just with these families, that it’s not worth it to fight. They know the end result,” Meaker said.

Immigrant families are gathering documents they need to return home

Countries with large populations living in the United States are seeing signs of more people wanting to return home.

Applications for Brazilian passports from consulates in the U.S. increased 36% in March, compared to the previous year, according to data from the Brazilian Foreign Ministry. Birth registrations, the first step to getting a Brazilian passport for a U.S.-born child, were up 76% in April compared to the previous year. Guatemala reports a 5% increase over last year for passports from its nationals living in the United States.

Last month, Melvin Josué, his wife and another couple drove four hours from New Jersey to Boston to get Honduran passports for their American-born children.

It’s a step that’s taken on urgency in case these families decide life in the United States is untenable. Melvin Josué worries about Trump’s immigration policy and what might happen if he or his wife is detained, but lately he’s more concerned with the difficulty of finding work.

Demand for his drywall crew immediately stopped amid the economic uncertainty caused by tariffs. There’s also more reluctance, he said, to hire workers here illegally.

(The Associated Press agreed to use only his first and middle name because he’s in the country illegally and fears being separated from his family.)

“I don’t know what we’ll do, but we may have to go back to Honduras,” he said. “We want to be ready.”

The size of the exodus and its impact on schools remains unclear, but already some are starting to worry.

A consultant working with districts in Texas on immigrant education said one district there has seen a significant drop in summer school sign-ups for students learning English.

“They’re really worried about enrollment for the fall,” said Viridiana Carrizales, chief executive officer of ImmSchools, a nonprofit that advises school districts how to meet the needs of immigrant students and their families.

Education finance experts predict budget problems for districts with large immigrant populations.

“Every student that walks in the door gets a chunk of money with it, not just federal money, but state and local money, too,” said Marguerite Roza, a Georgetown University professor focusing on education finance. “If a district had a lot of migrant students in its district, that’s a loss of funds potentially there. We think that’s a real high risk.”

Trump’s offer to pay immigrants to leave and help them with transportation could hasten the departures.

González, now back in Venezuela, says he wouldn’t have accepted the money, because it would have meant registering with the U.S. government, which he no longer trusts. And that’s what he’s telling the dozens of migrants in the U.S. who contact him each week asking the best way home.

Go on your own, he tells them. Once you have the cash, it’s much easier going south than it was getting to the U.S. in the first place.

____

Bianca Vázquez Toness, who speaks and Portuguese, has spent a decade writing about immigration or education. Associated Press writer Jocelyn Gecker contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s for working with philanthropies, a of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Bianca Vázquez Toness Of , Neal Morton And Ariel Gilreath Of The Hechinger Report And Sarah Whites-koditschek And Rebecca Griesbach Of Al.com, The Associated Press