An insolvent С����Ƶ forestry company’s attempt to sell off a forest licence to pay back creditors has triggered a dispute with several First Nations, who allege the company is attempting an “end run” around their rights.

This spring, three Indigenous groups — the Katzie and Peters First Nations, and the Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council — challenged the Teal-Jones Group before a С����Ƶ Supreme Court judge for attempting to complete an interim transfer of forest licence A19201 to Western Canadian Timber Products Ltd. (WCTP).

The move came before the С����Ƶ Minister of Forests could consult with 39 First Nations who have territory in the area. In a ruling released last month, Justice Shelley Fitzpatrick said the First Nations had argued Teal Cedar Products Ltd., a subsidiary of the Teal-Jones Group, was attempting to “blatantly circumvent” protections afforded to the three interested nations.

“They argue that this is really nothing more than a ‘back-door’ scheme to allow WCTP to operate under the licence on a long-term basis and to harvest timber without ministerial approval,” wrote Fitzpatrick.

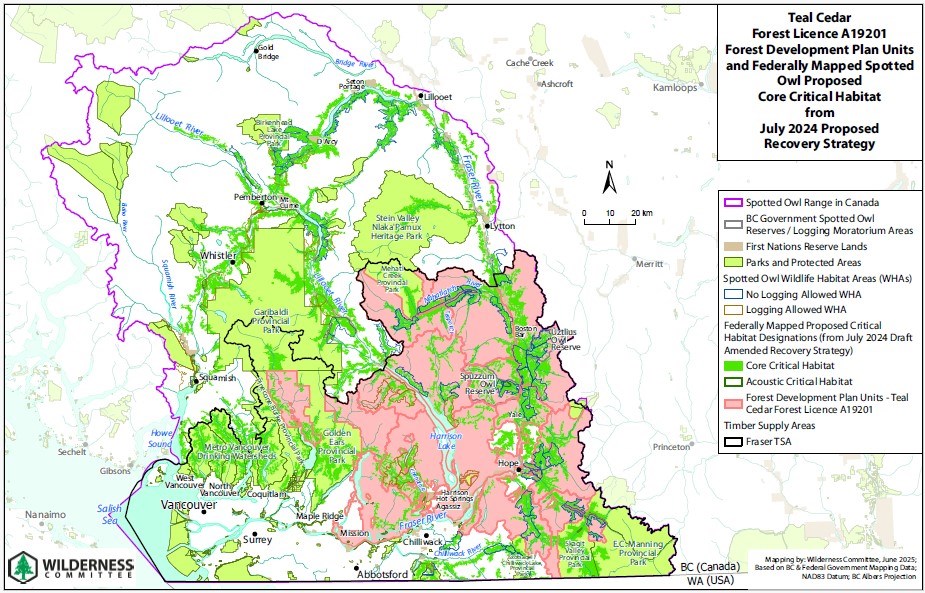

Forest licence A19201 spans a sprawling collection of Crown forest land in the Fraser Valley near Chilliwack, Pitt Lake, Harrison Lake and north of Hope. The licence gives rights to log nearly 315,000 cubic metres of timber a year — more than a quarter of the Fraser timber supply area’s annual allowable cut.

Fitzpatrick’s ruling — which ultimately sided with Teal-Jones and its creditors — came just weeks before the federal government released a long-awaited series of delineating core critical habitat for the northern spotted owl.

The species is Canada’s most endangered bird, with a single wild-born animal known to exist in the Fraser Canyon. After 18 years of delays and multiple federal court cases, the maps outline 400,000 hectares of core critical habitat meant to form the backbone of a recovery strategy.

About half of that federally mapped territory remains vulnerable to logging. Of that, 41 per cent — about 83,000 hectares of unprotected spotted owl territory — is contained in forest licence A19201, according to mapping from the non-profit Wilderness Committee.

The prospect of such a major transfer of logging rights in critical spotted owl habitat worries Joe Foy, the Wilderness Committee’s conservation and policy campaigner.

For years, Foy has mapped which companies are logging where in the area. The result: WCTP and its numbered companies appear to be the No. 1 logger of critical habitat of the endangered owl.

“It appears to us that Western Canadian timber products and companies associated with them — because they have numbered companies, too — is the No. 1 logger of spotted owl critical habitat as mapped by the federal government,” Foy said. “For me, that’s problematic.”

A spokesperson for the С����Ƶ Ministry of Forests said it has received an official request to transfer Forest Licence A19201 from Teal Cedar to WCTP.

Under the Forestry Act, the ministry is obligated to consider and respond to the request. A spokesperson said it would consult with First Nations before making its decision.

Judge rules interim transfer was fair

The legal dispute hinged on whether the proposed interim agreement between Teal Jones and WCTP triggered a duty to consult with First Nations.

Since the fall of 2024, the Katzie and Peters First Nations had put in bids to purchase parts of the licence, but were denied.

On the eve of the hearing, the Katzie First Nation put forward a letter seeking to adjourn the hearing so it could submit a formal offer. The letter indicated the offer would match many of the commercial terms of the WCTP agreement with a purchase price of $14.5 million.

But Fitzpatrick ruled Teal Jones’ agreement with WCTP remained “the highest and best offer presently available for consideration and approval after all that time.”

The judge concluded that the sales process had been conducted in a “fair and reasonable manner” and that those who wished to submit bids or offers had more than enough time to do so.

In an emailed statement, the Katzie First Nation told BIV the case is part of “ongoing political engagement” with the province and that it would not comment until the С����Ƶ government decides on the licence transfer.

Foy, who has worked extensively with First Nation leaders across the Fraser timber supply area over the years, said the transfer of the forest licence represents a retreat of promises to engage with Indigenous Peoples.

“This is a government that has rightfully promised reconciliation and building First Nations economies,” Foy said.

“This seems like a haywire deal when the people whose territories these are in are being steamrolled.”

Teal-Jones, WCTP and the other First Nations in the case did not respond to requests for comment.

The rise of Teal Jones

Founded in 1946 in Surrey, Teal-Jones Group began massively expanding its footprint in the 1990s. It purchased major timber forest licences in Haida Gwaii in 1999, and another on southern Vancouver Island in 2004.

Those forest lands fed a 400-worker mill in Surrey, one of the largest producing shake and shingle mills in the world.

Over the next two decades, the company expanded its operations into the United States, purchasing or building mills and acquiring forest rights across Washington state, Oklahoma, Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi.

In 2022, Teal Jones generated $644 million in consolidated revenue, held 880 acres of real estate and managed more than 800 employees. With 14 subsidiaries, the company had grown to become the largest privately owned timber harvesting and lumber manufacturer in the province.

Behind the scenes, however, revenue was not keeping up with costs. In April 2024, the company filed for creditor protection after it revealed it was in a desperate financial position.

A deep financial hole

Teal-Jones attributed part of its struggles to falling lumber prices. It also pointed to a “protracted demonstration” that cost it $40 million — almost certainly a reference to protests against logging old-growth forests at Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island.

In a separate March 31 ruling before the С����Ƶ Supreme Court, the company lost its bid to claim $75 million in damages after it alleged its logging rights had been effectively expropriated on Haida Gwaii.

Teal-Jones had challenged the С����Ƶ government and the Haida Gwaii Management Council, arguing it had engaged in the “constructive taking” of its property when it allowed the First Nation to block access to its tenures on the island.

The case dated back to 2010, when the province and First Nation signed the Land Use Objectives Order as a path to maintain the ecological integrity of the island’s forests and re-balance their management away from a model aimed purely at harvesting.

The judge dismissed the case, saying Teal-Jones had not been fully blocked from accessing its tenures. According to the ruling, the company still retained significant harvesting rights and the constraints were not equivalent to a full expropriation.

Over the past year, court-appointed monitors have launched multiple bids to sell off Teal-Jones’ assets so it can pay back lenders and creditors. The creditor protection process is also meant to help the company restructure so it can focus on its core operations, such as the Surrey mill, according to documents filed by its current monitor Ernst & Young.

Deal to benefit creditors and forestry companies

Operating the Surrey mill requires a steady supply of timber. The sale of forest license A19201 to WCTP was meant to secure that source of fibre, giving Teal-Jones a first right of refusal and a lifeline to get back on its feet, records show.

According to the two-step deal, WCTP is to pay Teal-Jones $14 million, and take on $3 million in liabilities and a $1.1 million annual government holding fee to maintain the licence.

Fitzpatrick approved the agreement with WCTP, granting it interim rights to log the forest licence until the Minister of Forests consults with First Nations and makes a final decision on the transfer.

The win for Teal-Jones comes as the company owes its creditors and lenders about $177 million. Among others, they include Wells Fargo, Royal Bank of Canada and Export Development Canada. The latter provided Teal-Jones’ U.S. operations with a more than $50 million loan in 2021, transaction records show.

Zoé de Bellefeuille, a spokesperson for the Crown corporation, declined to share how much it has recouped through the insolvency process, citing its transparency and disclosure policy.

However, court documents show interim lenders had provided $84 million by March 28, 2025 to allow Teal-Jones to maintain operations as it sells off its assets. According to the court ruling, there remains a collateral shortfall of about $53 million, with interim lenders at significant risk of not recovering the full amount of their loans.

Fitzpatrick said the quick sale of the forest licence to WCTP would benefit creditors and lenders, as well as the local economies where the group operators and does business.

That includes companies like Domtar and its Vancouver Island operations. As Canada’s largest forestry company, Domtar had an agreement with Teal Cedar to provide the mill with fibre.

Chris Stoicheff, a spokesperson for Domtar, said the loss of fibre from the Teal-Jones licence was significant and contributed to the indefinite curtailment of the mill’s paper operations in January 2024.

Under the interim agreement, WCTP is required to enter into a “substantially similar” deal to the one Teal Jones had with Domtar, so it can feed its Crofton mill with pulp logs.

Stoicheff said the proposed transfer of the forest licence has the “potential to improve fibre supply” to mills in the region. But due to “supply and demand market factors,” the company has no current plans to resume its Crofton paper operations, he added.

In her decision, Fitzpatrick pointed to the “current economic challenges” facing Canada and С����Ƶ, and how the forest licence transfer would benefit multiple forestry companies and their creditors.

“In an insolvency proceeding, it is generally considered that ‘time is money,’ in the sense that the longer the proceeding, the more expensive it becomes,” wrote Fitzpatrick.

Foy acknowledged that the deal would likely benefit some businesses at an economically difficult time for Canada.

But the timing of it, according to Foy, will form a critical test on two fronts: Whether the province follows through on its promises to engage with Indigenous Peoples, and whether it will work alongside the federal government to uphold the Species at Risk Act.

“This is another moment where we see — what are they going to do?” he said.